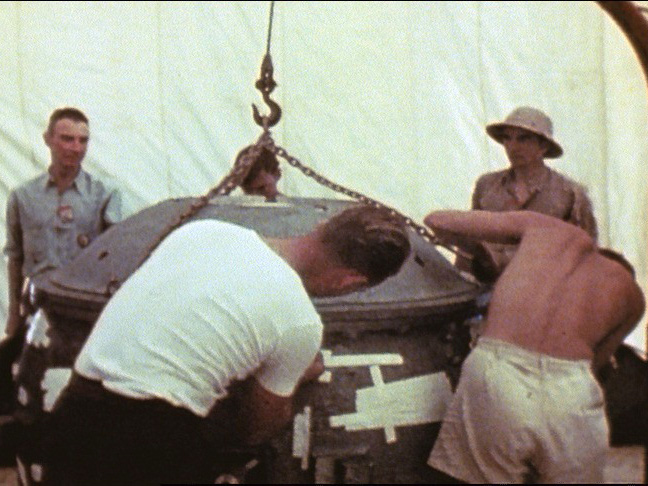

Oppenheimer with the ‘Gadget’ before the Trinity test. Courtesy http://www.atomicheritage.org.

Oppenheimer with the ‘Gadget’ before the Trinity test. Courtesy http://www.atomicheritage.org.AHF News:

At 5:29:21 MT July 16, 1945, Manhattan Project scientists conducted the world’s first atomic bomb test at the Trinity site near Alamogordo. The Atomic Heritage Foundation is pleased to feature dozens of audio/visual interviews with Trinity test eyewitnesses on the “Voices of the Manhattan Project.” From Manhattan Project director General Leslie R. Groves to scientists and soldiers, they recall the overwhelming force and terrifying beauty of the first nuclear explosion.

Scientists feared the “Gadget,” the plutonium implosion device, would not work.

“The physicists were very skeptical as to whether the lenses would work properly,” chemist George Kistiakowsky explained. “I bet [J. Robert] Oppenheimer quite a bit of my money, about six or seven hundred dollars against ten dollars, that the explosive part would work and there would be some nuclear reaction.”

He was right, and Oppenheimer paid him his due after the successful test.

Emilio Sègre, who would win the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1959, was one of the skeptical physicists. “I asked whether they were absolutely sure that the atmosphere wouldn’t catch fire,” Sègre said. “They tried to reassure me, but that thing was pretty fearful. I can’t say that I started to calm down!”

The military wanted to keep the Trinity test a secret, no matter what happened. Thomas O. Jones was a counterintelligence officer at Los Alamos.

“My role in that situation was to see whether this bomb went “pfump” or whether it took half of the state of New Mexico into the air and perhaps into flights around the world,” Jones said. “My role was to see that whatever happened, nobody noticed.”

Despite the enormous tension before the Trinity test, Groves proudly remembered that he remained calm and confident.

“At Alamogordo, we had about three hours or four hours to wait for the bomb,” Groves said. “The tents were flapping in the high wind. [James B.] Conant and [Vannevar] Bush were in the same tent with me. Afterwards they asked, ‘How on earth did you sleep? You went right to sleep while we stayed awake. With those tents flapping, how could you sleep?’”

A passing storm forced the test to be delayed for an hour. Finally, physicist Marvin Wilkening recalled the last few seconds. “There was a countdown by Sam Allison, the first time in my life I ever heard anyone count backwards.” Wilkening said. “We used welder’s glass in front of our eyes, and covered all our skin. When the countdown ended, it was like being close to an old-fashioned photo flashbulb.”

The sight of the explosion led to mixed feelings on the part of the eyewitnesses. “It was the most shocking, enormous explosion that I had ever seen,” William Spindel recalled. “I was about 20 miles away from the site. We were supposed to keep our eyes closed for the first ten seconds because of ultraviolet radiations.

“I estimated that at 20 miles away, the explosion traveling at the speed of sound would take about a minute to reach me. It was the most intimidating minute I have ever spent, seeing the terrible ball, growing and growing, enormous colors. What kind of blast could it be when it finally got to me? Fortunately, it wasn’t that great because I’m still here.”

Val Fitch, a member of the Special Engineer Detachment who would go on to the win the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1980, was amazed by the size of the explosion.

“It’s hard to overstate the impact on the senses of something like that,” Fitch said. “First the flash of light, that enormous fireball, the mushroom cloud rising thousands of feet in the sky, and then, a long time afterwards, the sound. The rumble, thunder in the mountains. Words haven’t been invented to describe it in any accurate way.”

Felix DePaula, a soldier at Los Alamos, was less impressed. “The [Trinity test] didn’t make a big impression on me, because the only thing I had ever seen in the way of explosives was firecrackers,” DePaula said.

”But an older man, Pop Borden, had worked with dynamite before he got into the service. Four days after the detonation, Borden still couldn’t eat because he was so upset about the detonation. ‘That’s the most terrible thing I’ve ever seen in my life,’Borden said. Borden could see the devastation that it could bring on because he had something to compare it to. “I had nothing to compare it to.”

For these interviews and more reflections on the test, visit “Voices of the Manhattan Project.”

The Atomic Heritage Foundation (AHF) is a nonprofit in Washington, D.C., dedicated to the preservation and interpretation of the Manhattan Project and its legacy. AHF has been working to create a Manhattan Project National Historical Park for nearly 15 years. Now that the park will be a reality,

AHF will continue its efforts to preserve historic sites and develop educational programming for park visitors, students, teachers, and the general public. For more information about the Atomic Heritage Foundation, visit http://www.atomicheritage.org/ .