PEEC Amateur Naturalist: Have You Seen a Bat Lately?

PEEC Amateur Naturalist: Have You Seen a Bat Lately?Bandelier National Monument once had a colony of bats at a cave roost along the cliff face in the Long House area.

Chris Judson, a park ranger, has been told that the colony has been present on and off from at least the 1930s.

The colony was not present in 1976, but was present from 1985 to 2002. Surprisingly, it did not return from its spring migration in 2003. It has not returned to the Long House cave since then.

Now-vacant bat cave entrance high on the cliff face of the Long House. Photo by Mary Caperton Morton

Now-vacant bat cave entrance high on the cliff face of the Long House. Photo by Mary Caperton Morton

There were times that the whole colony, or part of it, would move out for weeks and then return sometime later during the summer. It was clear that the bats were familiar with other caves suitable for their needs. Judson knows of one cave along the Falls Trail that the same colony did use, but there must be other caves as well.

Although not as dramatic as the huge number of bats that take flight at Carlsbad Caverns, it still was an impressive sight when an estimated 10,000 bats left their roost in the darkening evening. We hope that the colony will come back. In the meantime, it probably is somewhere not far away.

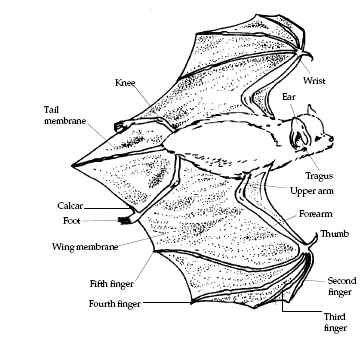

Imagine the bat in the sketch without its wings. As the two following photographs show, a bat is not very large when considered without its wings. The first photograph shows a bat with its wings folded. Its body is about the same length of the thumb of the person holding it ─ about three inches long. The second photograph shows a bat with one of its wings opened and it now appears much larger. The wings of a bat make it appear to be much larger compared to its body.

This bat with folded wings is about as long as a person’s thumb. Photo by Robert Dryja

This bat with folded wings is about as long as a person’s thumb. Photo by Robert Dryja A bat with extended wings is much larger. It would appear even larger if both wings were extended. Photo by Robert Dryja

A bat with extended wings is much larger. It would appear even larger if both wings were extended. Photo by Robert DryjaThere are nearly 40 species of bats in the United States and more than 20 species in New Mexico. There are at least 12 species in this area. One local species, the pallid bat, eats both fruit and insects.

There is a wide range in the size of bats when the whole world is considered. The giant Australian fruit bat has a five-foot wingspan while the bumblebee bat has a five-inch wingspan. A typical size for a bat therefore does not exist unless you are referring mostly to species of the local insect eating bats.

Australian Fruit Eating Bat. Photo by Adele Burgess

Australian Fruit Eating Bat. Photo by Adele Burgess

Bumblebee Bat. Photo by Daniel Hargreaves

Bumblebee Bat. Photo by Daniel Hargreaves Fruit eating bat. Photo by Tarun Das

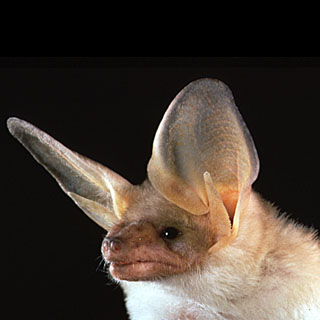

Fruit eating bat. Photo by Tarun Das Pallid bat. Photo by Merlin D. Tuttle/Bat Conservation International

Pallid bat. Photo by Merlin D. Tuttle/Bat Conservation InternationalEcholocation involves making various kinds of ultrasonic chirps that are reflected back to the bat. Chirps may last from 1/500 to 1/10 of second. During this brief time a bat may vary the frequency of its chirps in a narrow range of 40 to 55 thousand cycles per second. It also may vary the frequency over a range of 50 to 100 thousand cycles per second. We humans, in contrast, hear sounds best in the range of 3 to 5 thousands per second and typically cannot hear sounds over 20 thousand cycles per second.

Bats additionally can maintain the same constant frequency for their chirps or make a sequence of varying and constant frequency chirps. A bat will make a chirp about every tenth of a second when it’s searching widely for insects to eat. The rate increases to about two chirps every tenth of a second as it approaches an insect. It then becomes about three to six chirps every tenth of a second in its final approach. Bats may catch up to 500 insects an hour or about one insect every seven seconds thanks to this chirping.

Bats have evolved specialized ears in order to hear the echoes coming back from insects. Consider the following picture of a bat’s head. The ears are about the length of the bat’s head and cover about half the head as well. They also point forward in the same direction as the bat’s mouth.

Can you imagine if we humans had ears that were about a foot long and pointed forward over our eyes? This physical shape allows echoes to be focused in a thirty to forty degree range on each side of its mouth.

Close up of a bat’s head. Photo by Robert Dryja

Close up of a bat’s head. Photo by Robert DryjaWe can obtain a sense of what the chirps of bats sound like if we make a recording and then change the frequency so the sound becomes audible to us. You can listen to an audio file of a Mexican free-tailed bat at the following website: http://www.avisoft.com/sounds/bracken3.wav

Let the PEEC Amateur Naturalist know if you have seen bats or may even know of a roost. Perhaps a bat observation field trip can be arranged. The e-mail address is: naturalist@pajaritoeec.org.