Image by Pete Linforth/Pixabay

Image by Pete Linforth/Pixabay

By Douglas S. Thomas, an economist in the Applied Economics Office at NIST

The cyber world is relatively new, and unlike other types of assets, cyber assets are potentially accessible to criminals in far-off locations. This distance provides the criminal with significant protections from getting caught; thus, the risks are low, and with cyber assets and activities being in the trillions of dollars, the payoff is high.

When we talk about cybercrime, we often focus on the loss of privacy and security. But cybercrime also results in significant economic losses. Yet the data and research on this aspect of cybercrime are unfortunately limited. Data collection often relies on small sample sizes or has other challenges that bring accuracy into question.

In a recent NIST report, I looked at losses in the U.S. manufacturing industry due to cybercrime by examining an underutilized dataset from the Bureau of Justice Statistics, which is the most statistically reliable data that I can find. I also extended this work to look at the losses in all U.S. industries. The data is from a 2005 survey of 36,000 businesses with 8,079 responses, which is also by far the largest sample that I could identify for examining aggregated U.S. cybercrime losses.

Using this data, combined with methods for examining uncertainty in data, I extrapolated upper and lower bounds, putting 2016 U.S. manufacturing losses to be between 0.4% and 1.7% of manufacturing value-added or between $8.3 billion and $36.3 billion. The losses for all industries are between 0.9% and 4.1% of total U.S. gross domestic product (GDP), or between $167.9 billion and $770.0 billion. The lower bound is 40% higher than the widely cited, but largely unconfirmed, estimates from McAfee.

What makes the estimates startling is that, despite being higher than commonly cited values, the assumptions I used to calculate losses pushed the lower bound estimate down significantly, meaning the true loss may be much higher. I calculated the low value assuming that those who did not respond to the Bureau of Justice Statistics survey did not experience any losses. This amounted to 77% of the 36,000 businesses surveyed being presumed as having no loss; thus, the true loss is most likely higher than the low estimate.

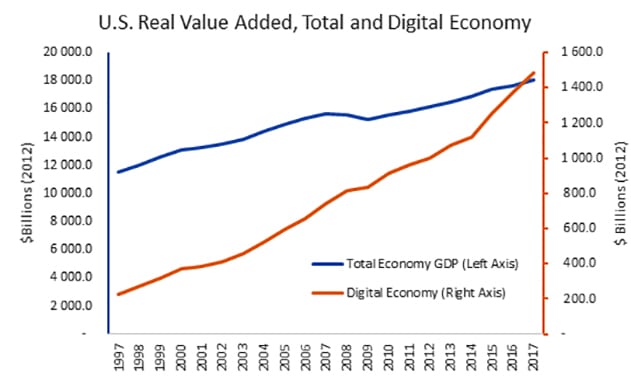

Additionally, the 2005 data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics comes from a time when cybercrime was considered to be less of a problem and the digital economy was smaller. If the Bureau of Justice Statistics data is representative, that is, if the average losses of the respondents’ companies equals the actual average U.S. losses per company, then the losses approach the high estimate of $36.3 billion for manufacturing and $770 billion for all industries.

This would make total cybercrime losses greater than the GDP of many U.S. industries, including construction, mining and agriculture. If the losses per company have increased faster than inflation, which is likely, then the losses would be even higher.

Chart by D. Thomas/NIST

Chart by D. Thomas/NIST

Most other estimates, including widely cited values, tend not to present technical details of data collection and analysis. Also, some estimates assume that the ceiling of cybercrime losses doesn’t exceed the cost of car crashes or petty theft in a given year. However, cybercrime is not comparable to other types of property crime or losses. Typical property losses require physical presence, which limits the loss or damage. For instance, a burglar must be physically present to steal an object from a home or business. Cyber assets, however, are potentially accessible to any would-be criminals on the planet without them needing to leave their homes.

The removal of this obstacle (the need for physical presence) is a game-changing factor for criminal activity, making cybercrime more prevalent. For example, my personal information (e.g., Social Security number) has been stolen countless times and my credit card information has been stolen and used on numerous occasions, but my house has never been burglarized and my car has only been broken into once. If I wanted to engage with a cybercriminal, I would only need to look in my email inbox, but I have no idea where I could find a burglar.

My report describes methods in detail, uses public data, and doesn’t assume the losses are similar to other types of crime. Since the data I used from the Bureau of Justice Statistics is from 2005, these estimates are likely low. The digital economy, measured in real dollars, grew 129% between 2005 and 2016, and I did not adjust for this increase. Additionally, the number of businesses, which is used for estimation, was lower in 2016, according to the Census Bureau’s Annual Survey of Entrepreneurs. This pushes my low estimate for losses down even further.

Economic growth in recent years for the U.S. has been between 2% and 3%, at least prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. While this is considered a healthy growth rate, my estimates show that the economy could be growing even faster if not for cybercrime. With the U.S. being a wealthy country and having a commonly spoken language that increases the number of potential offenders (it’s difficult to send phishing emails in an unfamiliar language), it’s a prime target for cybercrime.

If businesses and government underestimate the risk, they might underinvest in strategies for mitigating it. For instance, they might hire fewer IT security experts, take unnecessary risks with data/information, or disregard a recommended security measure. The result is unnecessary losses that may be quite substantial. If these losses are in the area of intellectual property, they can also reduce incentives for investing in research and development, limiting economic growth even more. For these reasons, it’s critical to gain a better understanding of cybercrime loss.

The implication from my report is that widely accepted estimates of cybercrime loss may severely underestimate the true value of losses. One of the first steps in addressing a problem such as cybercrime is to understand the magnitude of the loss, what types of losses occur, and the circumstances under which they occur. Without further data collection, we are in the dark as to how much we are losing. But the evidence suggests it’s more than we thought.