From left, retired National Weather Service Meteorologist Deirdre Kann; in-depth environmental journalist Laura Paskas; and David Stuart, an archeologist with lessons learned from the ancient Chaco Canyon culture in New Mexico, gave climate-related presentations Tuesday at the Society for Applied Anthropology conference in Santa Fe. Photo by Roger Snodgrass/ladailypost.com

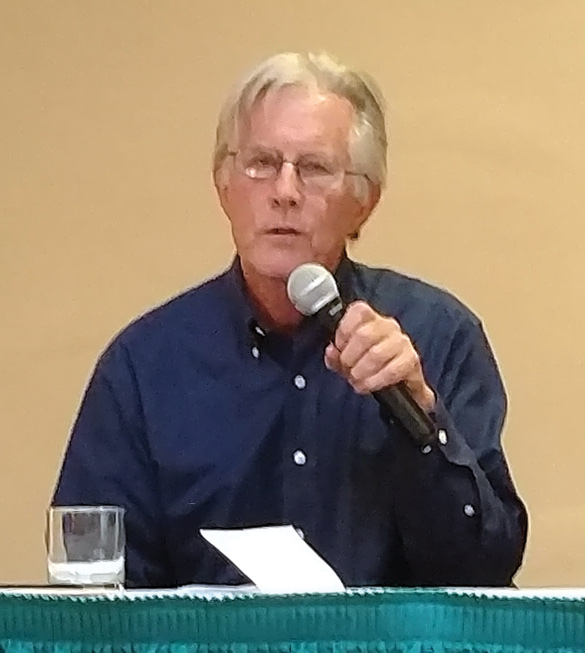

From left, retired National Weather Service Meteorologist Deirdre Kann; in-depth environmental journalist Laura Paskas; and David Stuart, an archeologist with lessons learned from the ancient Chaco Canyon culture in New Mexico, gave climate-related presentations Tuesday at the Society for Applied Anthropology conference in Santa Fe. Photo by Roger Snodgrass/ladailypost.com According to Bill deBuys, author and full-time humanist, climate change leads to an enervating depression trap. Photo by Roger Snodgrass/ladailypost.com

According to Bill deBuys, author and full-time humanist, climate change leads to an enervating depression trap. Photo by Roger Snodgrass/ladailypost.comBy ROGER SNODGRASS

Los Alamos Daily Post

In case there were any doubts that environmental concerns about global warming would take a back seat under a new period of assaults by the federal government, Lyla June Johnston does not agree.

A Diné (Navajo) woman, a poet and anti-coal power activist with a degree in environmental anthropology, she works with New Energy Economy to help realize the recently announced early closure plans of the two major power plants in the Four Corners area of New Mexico and Arizona. She said this week at an international meeting in Santa Fe that having “an activist DNA” means challenging the status quo and “constantly doing two things: exposing and dismantling what doesn’t work and building and nourishing what does.”

Johnston said she found it hard to account for how “the Zia symbol state” (with the sun sign) of New Mexico could derive only three percent of its energy from solar, with 60 percent from coal and 20 percent from nuclear,” but she also understood quite clearly that climate change has tied a lot of things together and that “Creator sent us a drought to give us the courage to change.”

Johnston’s talk was part of an annual meeting of the Society for Applied Anthropology in Santa Fe with some 2,000 members expected to attend. On Tuesday residents of Northern New Mexico were treated to a free day of topics of local interest. Thirty-five sessions ran the gamut from cultural diversity and preservation to contemporary art and ancient traditions; land, water and agricultural ecologies; health, education, economic and social justice issues; and vintage anthropological documentaries, among many others.

A discussion on the question of the survival of the Southwest under the looming threat of a changing climate seemed particularly timely in light of official announcements coming out of Washington, D.C. earlier in the day. President Trump signed an executive order intended to pull the plug on carbon emission regulations and reverse the modest constraints ordered late in the administration of his predecessor to reduce greenhouse gasses that are blamed not only for the warming, but also for the longer term prospects of extreme weather events and climate change.

Contrary to the current direction of national policy, Deirdre Kann, recently retired, former science and operations officer for the National Weather Service in Albuquerque, laid out a torrent of statistics supporting the opposite point of view. In short order, she provided some notable matters of fact among the local data points from Albuquerque, including these:

- Between 1950 and 2015, 8 of the 10 warmest years occurred;

- 1992 was the last year in which the temperature was lower than average, which means we have had 24 years of higher than average temperatures since then;

- The last full month, February 2017, was the second warmest month on the record that goes back 120 years;

- 2016 was the third consecutive hottest year ever – 2014 , 2015, 2016;

- 8 out of 12 months in 2016 were the warmest months; and

- 2001-2010 warmest decade on record.

“We are at a point where climate change and global warming are a well-documented reality,” she said.

Another speaker on the climate panel has taken a deep look at the conflicting pattern between state and federal policies so far this century. Teaming up with In Depth New Mexico journalist Laura Paskas spent much of last year criss-crossing the state investigating how that conflict has affected climate and warming practices in the local ecology.

During the Richardson years the New Mexico Environment Department was open to climate change concerns and somewhat effective in guarding against the George W. Bush administration’s crusade against climate science. Early in his first term, Bush reversed his position on regulating carbon dioxide emissions from coal-fired power plants and then unilaterally withdrew from the global Kyoto climate change treaty.

At the end of the Obama administration, the Paris Treaty on global cooperation to reduce warming was celebrated as a positive step by many environmentalists, but back in New Mexico, Republican Gov. Susana Martinez rolled back mitigation and adaptation policies, while undermining science and public input.

The gloves may be coming off in the changing currents of the local-national climate debate. David Stuart, an archeologist and a UNM professor who has written books on “Anasazi America” and “The Ancient People of Pajarito Plateau,” drew some explicit parallels between the fall of the great culture that flourished in Chaco Canyon and the speculative plans of current governing authorities.

“So when you increase the military by 10 percent, and we’re going to reduce taxes for billionaires by 20 percent and taxes for corporations by 35 percent. you are talking about what happened in Chaco in the 10 hundreds AD.” he said. “In modern America, we’re in this failing to sneeze mode.” Sneezing could help relieve some of the annoying symptoms.

Stuart’s interpretation of the Chacoan collapse and eventual abandonment blamed “cascades of small factors,” imperceptible changes that grow into another problem if they are not solved. In Chaco, in such a delicate water regime, where, “in two or three years of sub-par rainfall, you lose ground cover, then lose the possibility to go back to foraging,” he said. “The great house elites were 2 inches taller than the farmers,” because the workforce was not well treated.

Stuart’s moral has a lesson for the contemporary world: “All solutions in the big evolutionary perspective save warfare and massive famines come from the combination and ecology of small numbers,” which could be alleviated with greater attention to the small things. For the moderns, it is about small steps, such as converting to low-flow water systems, pushing back with tiny increments of energy savings and efficiencies, he suggested.

Bill deBuys anchored the panel and ably pulled it together at the end, countering the subject’s gloomiest tendencies by reminding participants of their humanity with abiding strengths. The former chairman of the Valles Caldera Board of Trustees and highly regarded author of eight non-fiction books, including “A Great Aridness” on climate change and “The Last Unicorn” on extinction, said change was natural and inevitable. The drought can become the new normal and the drought can have a worse drought, but humans can be amazingly strong and creative even under hardship.

“So much beauty remains in our land, the creatures and the human beings,” he said.

He passed along the advice of Environmental stalwart Bill McKibben. When asked what we needed to confront climate change, deBuys said, McKibben answered, “A strong community.” Asked how to get a strong community, McKibben said, “You build it.” And how that could be done, he said, was by understanding their common interests.

As far as making elaborate plans, deBuys said he was reminded of an old Jewish proverb: ‘If you want to make God laugh, tell her your plans.”