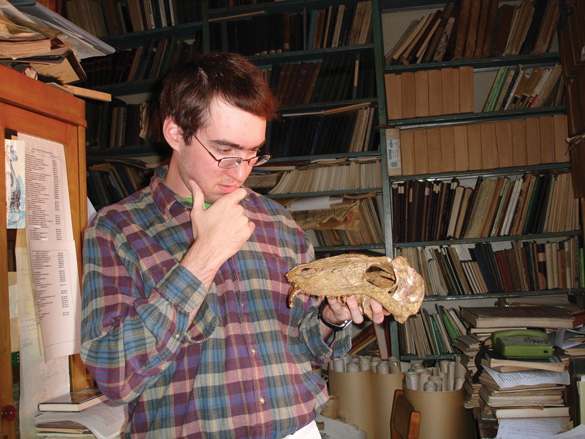

Christian Kammerer is a paleontologist at the Museum fur Naturkunde (Museum of Natural History) in Berlin, studies mass extinctions and the ancestors of mammals. The photo was taken with a timer in the Paleontological Institute in Moscow while he was examining fossils of mammal-related ancestors from the Ural Mountains. Courtesy photo

Christian Kammerer is a paleontologist at the Museum fur Naturkunde (Museum of Natural History) in Berlin, studies mass extinctions and the ancestors of mammals. The photo was taken with a timer in the Paleontological Institute in Moscow while he was examining fossils of mammal-related ancestors from the Ural Mountains. Courtesy photo Artist’s recreation of Bulbasaurus by M. Celeskey. Courtesy image

Artist’s recreation of Bulbasaurus by M. Celeskey. Courtesy imageBy ROGER SNODGRASS

Los Alamos Daily Post

Naturalists worry about endangered species and the threat of a sixth great extinction in the contemporary world, which some fear might sweep our own existence into the dustbin of time. But one paleontologist has given that scenario a twist, by salvaging a worthy species that died long ago.

The bones of what would eventually be defined as a four-legged, plant-eating creature with a big, bulbous, turtle-looking beak and a compact, porky body were uncovered by royal engineers who were constructing a military road near the Cape of Good Hope in Southern Africa in the mid-nineteenth century. An engineer named A.G. Bain, who was involved in the operation, reported that a large number of unknown reptile bones had been uncovered and that they would soon be sent to London.

They knew that their find included a “new order of animals,” remarkable for having “two teeth, or rather tusks, in the upper jaw and none whatsoever in the lower jaw,” Bain observed. “Their jaws were doubtless covered with a horny serrated substance, like the turtle.” But little did they know back then that the fossils were hundreds of millions of years old.

Matt Celeskey, an exhibit designer and paleontological illustrator, said of the fossils:‘They lived their lives with the other animals around them as individuals connecting to individuals. Somehow they speak to me across the eons.’ Photo by Roger Snodgrass/ladailypost.com

Matt Celeskey, an exhibit designer and paleontological illustrator, said of the fossils:‘They lived their lives with the other animals around them as individuals connecting to individuals. Somehow they speak to me across the eons.’ Photo by Roger Snodgrass/ladailypost.com

Matt Celenskey, the Santa Fe artist who recently worked with a German paleontologist to recreate one of these beasts said, “Nature has tried all different ways of eating, and these guys, the best we can tell, cropped plants and then would slice them up or grind them up by pulling the jaw back and forth. Like a cow moves its jaw from side to side, they had more forward and backward movement, a very distinctive kind of food processing,” he said. “With those big muscles in its head, it would have been a pretty powerful bite, almost like bolt cutters.”

The shipment of bones from South Africa arrived in England in January 1845 and were given the generic name dicynodont (“two-toothed dog”) by Richard Owen, a biologists with the Royal Geological Society, who believed them to be reptiles, but was troubled by the tusks, which he thought resembled elephant tusks, among a number of anomalies which made them seem unlike any other reptiles, while “anticipating conditions of mammals.”

Later researchers would establish that these fossils were not early reptiles, but rather early and distant relatives of mammals, as the discoverers might have intuited but could not quite believe.

Sorting out the “wastebasket” and filling the gaps

A research scientist at the Museum fur Naturkunde (Museum of Natural History) in Berlin, Christian Kammerer is an American specialist in vertebrate paleontology who received his PhD from the University of Chicago, followed by postdoc work at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

The specimen upon which the new species, Bulbasaurus phylloxyron is based, discovered and photographed by Roger M.H. Smith. (A) Front view, (B) Right semi-side view, and (C) left side view. Scale bar equals 5 cm. (From Kammerer CF, Smith RMH. (2017) “An early Geikiid dicynodont from the Tropidostoma Assemblage Zone (late Permian) of South Africa”. PeerJ 5:e2913. Courtesy photo

The specimen upon which the new species, Bulbasaurus phylloxyron is based, discovered and photographed by Roger M.H. Smith. (A) Front view, (B) Right semi-side view, and (C) left side view. Scale bar equals 5 cm. (From Kammerer CF, Smith RMH. (2017) “An early Geikiid dicynodont from the Tropidostoma Assemblage Zone (late Permian) of South Africa”. PeerJ 5:e2913. Courtesy photoKammerer is interested the whole group of dicynodonts, as a part of an ambitious research program on diversity and evolution of early relatives of mammals in the Permian and Triassic periods, between 290 million and 200 million, or so, years ago. This was a time when there were no mammals and no dinosaurs, although there were antecedents of both, who would slip through the extinctions and evade the dead ends, to evolve and diversify.

How did that happen and what did it mean in evolutionary terms?

These mammalian predecessors, including more directly related human ancestors, are called synapsids, and Kammerer is one of the leading synapsid specialists in the field.

In an email exchange from Berlin, he summarized some of the fundamental challenges of trying to study the causes and effects of ancient mass extinctions, for example.

“We paleontologists are greatly limited by the amount of exposed rock on the earth,” he wrote. “If we want to study a particular phenomenon in deep time (e.g., a mass extinction), we have to deal with the fact that only a tiny percentage of the global land surface, A. preserves the right-aged rocks, and B. contains fossils; and if you work on land animals, rather than sea creatures, that percentage is even smaller.”

The result is the potential for distorted information. So many of the land animal fossils (like Bulbasaurus) have been found in South Africa, he noted, that it is hard to generalize the findings to a global scale. But in more recent fieldwork in northeastern Brazil, where some rich fossil beds are just now coming to light, the evidence from Permian period deposits of the same age has been similar, “which helps confirm some of those extrapolated trends,” Kammerer wrote.

Another analytical hazard that Kammerer has had to resolve is that scientists in the 19th and early 20th century were not very disciplined when it came to classifying certain animals.

“One particularly notorious case is the genus Dicynodon, which became over time what we call a ‘wastebasket’ taxon, which means any ill-defined new species was tossed into this genus if you didn’t have any better idea of what might be its closest relative,” Kammerer said. “Although Dicynodon was named in 1845, it was not subject to serious taxonomic revision until 2011, when some colleagues and I published a total overhaul of the genus.”

Before the category was better understood there were 168 named species of Dicynodon, most of them from the Karoo Basin of South Africa, where many of these purported species were found. After the revisions, there were only two, Kammerer noted.

“The fact that there are still new species to discover there is testament to the incredible fossil richness of the region,” Kammerer said. “Beyond just being a new species, Bulbasaurus is important because it fills a gap in the fossil record. It is the earliest member of a group called the geikiids, which include some of the largest Permian dicynodonts.” But their origins have been hard to trace in the physical record, except by hypothesizing a “ghost lineage.” Now there is a real connection.

The new species was named Bulbasaurus for the bulbous swelling – known technically as “bosses” – on their snouts and phylloxeron (or “leaf-razor”) for the sharp edge of the jaw they used to slice their food.

The public was quick to catch the reference to a fictional creature Bulbasaurus in the popular Pokémon media franchise. Bulbasaurus in that context is a blue-green reptilian creature with a solar power seed on his back. Kammerer neither emphasizes the pop connection nor avoids it, except to say that wider public awareness of the animals’ existence is “always welcome,” especially given their unsung success and prominence for so long. “Dicynodonts were the dominant vertebrate herbivore for millions of years and are our own distant cousins,” he said.

Recreating Bulbasaurus

Just about everybody knows about dinosaurs, but not everyone knows about the creatures who populated the earth for a hundred million years before the dinosaurs and mammals began to take hold of the environment. Another device that helps connect the public to the older generation of animals is a credible life-like image of the subject.

Matt Celeskey, an illustrator and museum exhibit designer who works with the Museum of New Mexico, said he met Kammerer about a year ago when the researcher was visiting American collections.

What inspired Celeskey was the chance to portray a group of animals who are still barely known. Dicynodonts have been overshadowed by the dinosaurs who would rule the planet in the next phase and who have been the focus of so much attention in the last forty years. Drawing the lesser-known dicynodonts out of the shadows, “That’s particularly interesting to me,” he said.

“I knew roughly the kind of animals [Kammerer] was working with, not what he was going to name them or any of the details,” Celeskey said. Based on pictures of the fossils, and where the muscle masses are located, he began working up some sketches of the anatomy. Almost lost in what seemed at first like undifferentiated rocks are the details of a neck and shoulder area, a skull, a snout and lower jaw.

“Here’s the eye and here’s the broad back of the skull and the little chain of the neck vertebrae and a little bit of the shoulder and upper arm toward the back,” he said, pointing to features only a trained eye could see. “It’s always a fun challenge.”