Spotter planes on the USS Arizona. Courtesy photo

Spotter planes on the USS Arizona. Courtesy photoBy TERALENE STEVENS FOXX

Los Alamos

My grandmother, Effie Hedges, lived until she was 95 years old but she never recovered from the tragedies of loss of her children, particularly Teddy, her youngest, among those lost on the USS Arizona at Pearl Harbor.

Her first child died at the age of four after eating the poisonous wild parsnip along a stream in the wilds of Idaho, a story of grief and tragedy in itself. Her only girl died in her 40s of colon cancer. That left only my father, Jay, alive. Ironically, he too died just weeks after her death. He was 69, she was 95.

But here I want to tell you the story of my uncle, Theadore Roosevelt Stevens, a machinist mate on the Arizona. He was born at home in a small town in Southern Idaho, Howe, where his father had homesteaded. He was the son of Effie and Frank Stevens, farmers. Effie, my grandmother, married 40 year old Frank Stevens at the age of 16. By 1941, she was remarried and living in Eagle, Idaho.

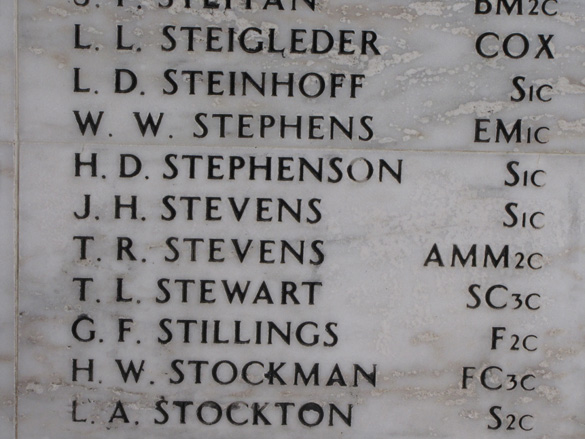

I never asked why they called their last child Theadore Roosevelt Stevens. However, maybe it was because the year Teddy was born was the year Theadore Roosevelt, the 26th president of the United States, died. Or maybe he was someone she admired. Teddy left to join the Navy on Sept. 7, 1937 and was assigned to the Arizona. He was a skilled mechanic and was responsible to keep the small spotter planes serviced. He was a young man full of hope. But his life ended on that “day of infamy.” His remains are among those lying at the bottom of the ocean. He was just 22.

Today it is hard to imagine the agony of not knowing whether your son or daughter is alive or dead for months. Deaths of military personnel are communicated quickly today. That, however, does not lessen the pain. But in 1941, communication was not what it is today. There was no Internet, cell phones, real-time visual reports or other. It took months to communicate to families the loss of their loved ones. Security was tight and information held close.

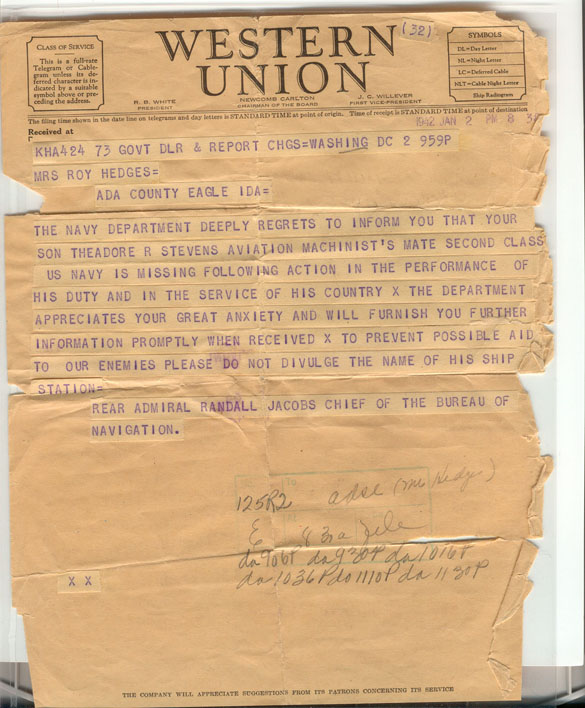

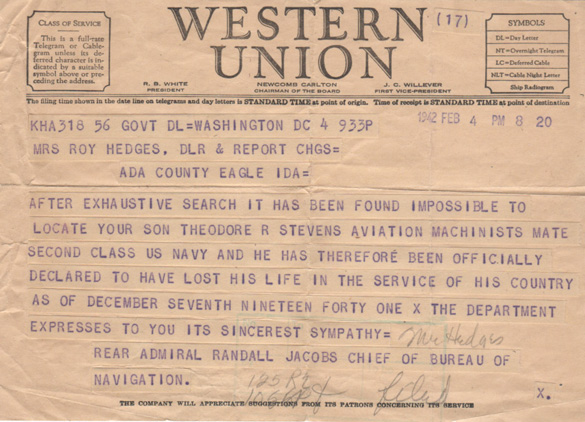

The first telegram came Jan. 2, 1942. Note it does not tell her he died but was missing in action. She was not to even tell anyone what ship he was on. The confirmation or the recognition that most were lost on the USS Arizona did not come for months. To her, the agony of not knowing was nearly unbearable. The family was pulled by dread of loss and a sense of hope that the reality was not true. Some sailors survived because they were on leave on-shore and some jumped as the ship sank. Perhaps he was one of them. But time went on without word and the hope faded. The final word came. He was among the dead.

When my grandmother died, all the information about her three deceased children was in an envelope. Within the envelope were the obituaries, telegrams and pictures.

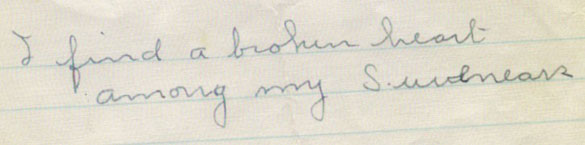

Along with all that, there was a handwritten note:

As a mother, myself, I came to understand her grief and the agony of her loss. I understood more about her broken heart and how she carried it as one of the deepest burdens a mother can carry. Every Dec. 7 she would take flowers to the Boise River and throw them in the river in the memory of her son.

Sailor Teddy. Courtesy photo

Sailor Teddy. Courtesy photo Name on the Wall of the Arizona Memorial. Courtesy photo

Name on the Wall of the Arizona Memorial. Courtesy photo Telegram. Courtesy photo

Telegram. Courtesy photo Second Telegram. Courtesy photo

Second Telegram. Courtesy photo